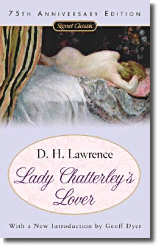

Exhibit "A" in Steyn's argument is D.H. Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover.

In 1960, 200,000 copies of Lady Chatterley's Lover were sold in Britain on the first day the ban was lifted--in part because of the treasures therein implied by Mervyn Griffith-Jones, prosecuting counsel, in his famous question to the jury: "Is this a book you would wish your wife or servants to read?"Today, even thirteen-year-old boys could not be tempted by the prosecutor's unintended come-on.

Yet the promiscuity that seems to trouble Steyn more involves not sex but commas. Of course, to interest us in his (justified) punctuation peeve he wraps his complaint around a disagreement about how well Alan Furst writes about sex. Steyn quotes two New York Times reviewers who claim that Furst is especially adept at sex scenes, but then cites an Atlantic Monthly reviewer who argues just the opposite. And Steyn provides a few examples from Furst's novels to support the latter.

Tom Wolfe, Ian Fleming, and Judith Krantz get the treatment, too.

Steyn's article is good clean fun: check it out.

Of course, Steyn and I are probably not helping by perpetuating what is almost certainly a wrongheaded apprehension of Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover. The novelist Doris Lessing, in her fascinating introduction to the new Penguin Classic edition of Lady Chatterley's Lover, suggests that novel, created in the shadow of war as Lawrence was dying of tuberculosis, is a plea for intimacy and one of the most powerful anti-war novels ever written. Click here to read an edited version of Lessing's introduction in The Guardian.

--Marshal Zeringue