After Allen Ginsberg’s reading of “Howl” on October 6, 1955 at the Six Gallery in San Francisco, Lawrence Ferlinghetti sent him a note, repeating Emerson’s message to Whitman upon reading Leaves of Grass: “I greet you at the beginning of a great career.” But Ferlinghetti added a line: “When do I get the manuscript?”

--from "A History of Howl" at the City Lights website

Ferlinghetti got the manuscript and in 1956 published the first edition of Howl and Other Poems.

James Sullivan, whose Boston Globe review of The Poem That Changed America: "Howl" Fifty Years Later, edited by Jason Shinder, appears here, wrote:

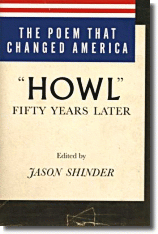

The Poem That Changed America goes a long way toward answering what "Howl" meant and what it has come to mean, with essays by Rick Moody ("On the Granite Steps of the Madhouse with Shaven Heads"), Sven Birkerts ("Not Then, Not Now"), Billy Collins ("My 'Howl'"), Phillip Lopate ("'Howl' and Me"), Marge Piercy ("The Best Bones for Soup Have Meat on Them"), Robert Pinsky ("No Picnic"), and many more.Fifty years later, the Beat Generation's most famous poem--arguably the most influential poem of any kind of the 20th century--has, like its late creator, come to represent a quaint notion of social-outsider status, an ecstatic, overly earnest, easily parodied celebration of self-destructive youth.

Or has it?

Greil Marcus reviewed The Poem That Changed America for the New York Times; click here to read his review.

Ginsberg died in 1997; click here to read his New York Times obituary.

Ferlinghetti had the foresight to contact the ACLU before publishing "Howl," correctly anticipating it might be censored. As part of ACLU Banned Books Week 2001, he discussed the publication of the book and the ensuing obscenity trial. Click here to listen to his remarks.

--Marshal Zeringue