I am an avid follower of

John Dickerson's political journalism which used to appear in

TIME magazine and is now featured at

Slate.

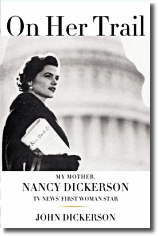

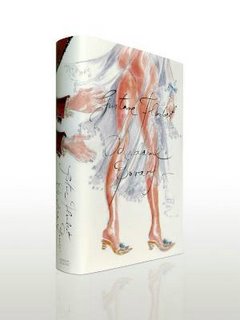

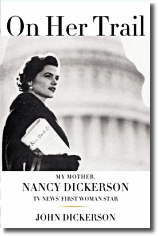

His new book is

On Her Trail, the story of his mother, Nancy Dickerson, the first woman to break into the all-male business of TV news. If you are like me when I first heard about the book, you may think this is a certain kind of book--an admiring, probably uncritical, portrait. You would be wrong.

I asked John to apply the "

page 69 test" to his book. Here is what he reported:

If you open to page 69 of On Her Trail you find yourself at the start of Chapter Nine. It’s helpful for my purposes that you’ve come to this page because this book about my mother Nancy Dickerson is more than just the story of her life in journalism. It is the story of how her son, with whom she had an occasionally rocky relationship, discovered her after she died. If you pay attention only to the lovely pictures on the cover and on the inside you’re likely to think this is just one long glowing portrait of a mother from an adoring son. It’s more complicated and hopefully interesting than that.

On page 69 I’m in the Wisconsin countryside visiting my aunt Mary Ellen Philipp on an old dairy farm where she vacations. My cousins are these wonderful people with whom I had fallen out of touch. After Mom’s death and the death of their father we spent more time together. Though the Dickerson family had grown up in a more rarified atmosphere, my brother and I blended in with their world pretty quickly: “Whether it was in Milwaukee or Washington, the grandchildren of Fred and Florence Hanschman were familiar with cocktail hour, or as other people call it, lunch.”

The real discoveries from this trip were found under the stairs of the farm’s granary where I found a packet of my mother’s letters, old newspaper clippings and photographs. My mother had been famous before I was born. By the time I was old enough to know what the nightly news was she was largely off television. These newspaper clippings gave me some clue about just what a phenomenon she had been and since most of them were written with the amazement usually reserved for child prodigies and dog acts, the clippings also gave me a feel for the time in the late 50s and 60s where a woman working in a man’s world was treated with condescension even when she was being praised.

The only thing missing from this page is a sense of the historical anecdotes in the book—behind the scenes stories of LBJ the night after Kennedy was killed, Nixon calling my mother in the middle of the night, and the atmosphere in the city during the 50s and 60s. One hopes though that after you read page 69 you’ll want to turn it and get to that stuff soon enough.

Many thanks to John for the input.

John writes more about the book and his research in

this Slate article.

Click

here to read an excerpt from

On Her Trail.

Howard Kurtz interviewed John about

On Her Trail on CNN's "Reliable Sources" this morning. Click

here to read the transcript of the interview.

On October 19, John filed a NPR "Day to Day" segment on Nancy Dickerson's pathbreaking role in television journalism. Click

here to listen to that report; also at that link, listen to a phone conversation from February 18, 1964, in which Lyndon Johnson rebuffed Nancy Dickerson's request to photograph Jack Valenti for a report.

John Dickerson is apparently Washington's

real uniter-not-divider: after all, who else writes a book that is praised by both Peggy Noonan and Al Franken? To read these endorsements and more reviews, click

here.

Catch up with John's

Slate journalism

here, and his articles in

TIME here.

Previous "page 69 tests":

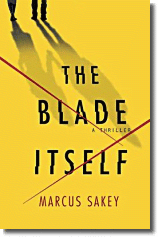

Marcus Sakey, The Blade ItselfRandy Boyagoda, Governor of the Northern ProvinceJohn Gittings, The Changing Face of ChinaRachel Kadish, Tolstoy LiedEric Rauchway, Blessed Among NationsTim Brookes, Guitar and other booksRuth Padel, Tigers in Red WeatherWilliam Haywood Henderson, Augusta LockeJed Horne, Breach of FaithRobert Greer, The Fourth PerspectiveDavid Plotz, The Genius FactoryMichael Allen Dymmoch, White TigerPatrick Thaddeus Jackson, Civilizing the EnemyTom Lutz, Doing NothingLibby Fischer Hellmann, A Shot To Die ForNelson Algren, The Man With the Golden ArmBob Harris, Prisoner of TrebekistanElaine Flinn, Deadly CollectionLouise Welsh, The Bullet TrickGregg Hurwitz, Last ShotMartha Powers, Death AngelN.M. Kelby, Whale SeasonMario Acevedo, The Nymphos of Rocky FlatsDominic Smith, The Mercury Visions of Louis DaguerreSimon Blackburn, LustLinda L. Richards, Calculated LossKevin Guilfoile, Cast of ShadowsRonlyn Domingue, The Mercy of Thin AirShari Caudron, Who Are You People?Marisha Pessl, Special Topics in Calamity PhysicsJohn Sutherland, How to Read a NovelSteven Miles, Oath BetrayedAlan Brown, Audrey Hepburn's NeckRichard Dawkins, The Ancestor's Tale--Marshal Zeringue

their twenties. What’s not to like?