Her entry begins:

Her entry begins:Familiar feelings: Tired, anxious to return home, in need of one more stretch before boarding a plane. Expectations low, I strolled through the airport bookstore and scanned the shelves. Then I spied two familiar names and a novel I had missed when it first appeared. Purchase made. Electronic reading device stowed. Comfort located within two paper covers.About Science on American Television, from the publisher:

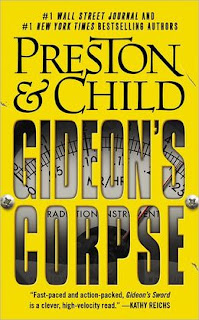

Thank you Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child. Your Gideon's Corpse sustained, entertained, and informed me all the way home, just as your other novels (beginning with Relic) have done through the years. The air-hours dwindled as your physicist-hero careened through whitewater and cadged his way into secure government facilities, attempting to derail a terrorist plot. When there was...[read on]

As television emerged as a major cultural and economic force, many imagined that the medium would enhance civic education for topics like science. And, indeed, television soon offered a breathtaking banquet of scientific images and ideas—both factual and fictional. Mr. Wizard performed experiments with milk bottles. Viewers watched live coverage of solar eclipses and atomic bomb blasts. Television cameras followed astronauts to the moon, Carl Sagan through the Cosmos, and Jane Goodall into the jungle. Via electrons and embryos, blood testing and blasting caps, fictional Frankensteins and chatty Nobel laureates, television opened windows onto the world of science.Learn more about Science on American Television at the University of Chicago Press website.

But what promised to be a wonderful way of presenting science to huge audiences turned out to be a disappointment, argues historian Marcel Chotkowski LaFollettein Science on American Television. LaFollette narrates the history of science on television, from the 1940s to the turn of the twenty-first century, to demonstrate how disagreements between scientists and television executives inhibited the medium’s potential to engage in meaningful science education. In addition to examining the content of shows, she also explores audience and advertiser responses, the role of news in engaging the public in science, and the making of scientific celebrities.

Lively and provocative, Science on American Television establishes a new approach to grappling with the popularization of science in the television age, when the medium’s ubiquity and influence shaped how science was presented and the scientific community had increasingly less control over what appeared on the air.

Marcel Chotkowski LaFollette is an independent historian based in Washington, DC.

Writers Read: Marcel Chotkowski LaFollette.

--Marshal Zeringue