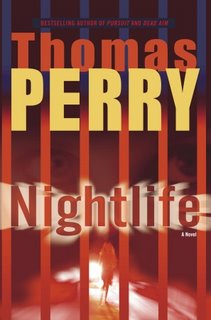

In a featured blurb for

Thomas Perry's

Nightlife, Stephen King writes: "I can't imagine any reader finishing this and thinking he or she didn't get his money's worth. And it's scary! I say that with deep admiration."

When Stephen King says a book is scary you might think of

a once-friendly-St. Bernard-turned-killer or any number of other terrifying, otherworldly forces.

But

Nightlife isn't scary like a Stephen King novel: rather, it's scary like Shakespeare is scary, its menace is all too believable in this world of ours.

Nightlife's villain is real and believable, and that makes her psychopathology all the more compelling. Not that this kind of killer lurks on every corner. But two of the things I like about Perry's thrillers are that he develops characters instead of caricatures, and there are very few of those plot moments that make me think, "as if

that would happen" or "Why doesn't the killer just [whatever]?" Even excellent thriller writers have to occasionally flirt with improbable actions and incredible coincidences, and there are a couple of times when it seems that Perry will take that way out. But not many.

I usually like my thrillers more rather than less plausible, and Perry delivers.

There is more that I wanted to write about this novel but every day that I've not done so feels like a day that I'm cheating a reader who might enjoy the thriller as much as I did. So click

here to read Janet Maslin's review (with which I more or less agree) to find out more about the story.

To read an excerpt from

Nightlife, click

here.

I have more to write about one of Perry's characters (from a different novel) in the blog's embryonic

series on the coolest women in crime fiction written by men, so stay tuned.

--Marshal Zeringue